The Wendigo: Truth, Origins, and What the Legends Really Say

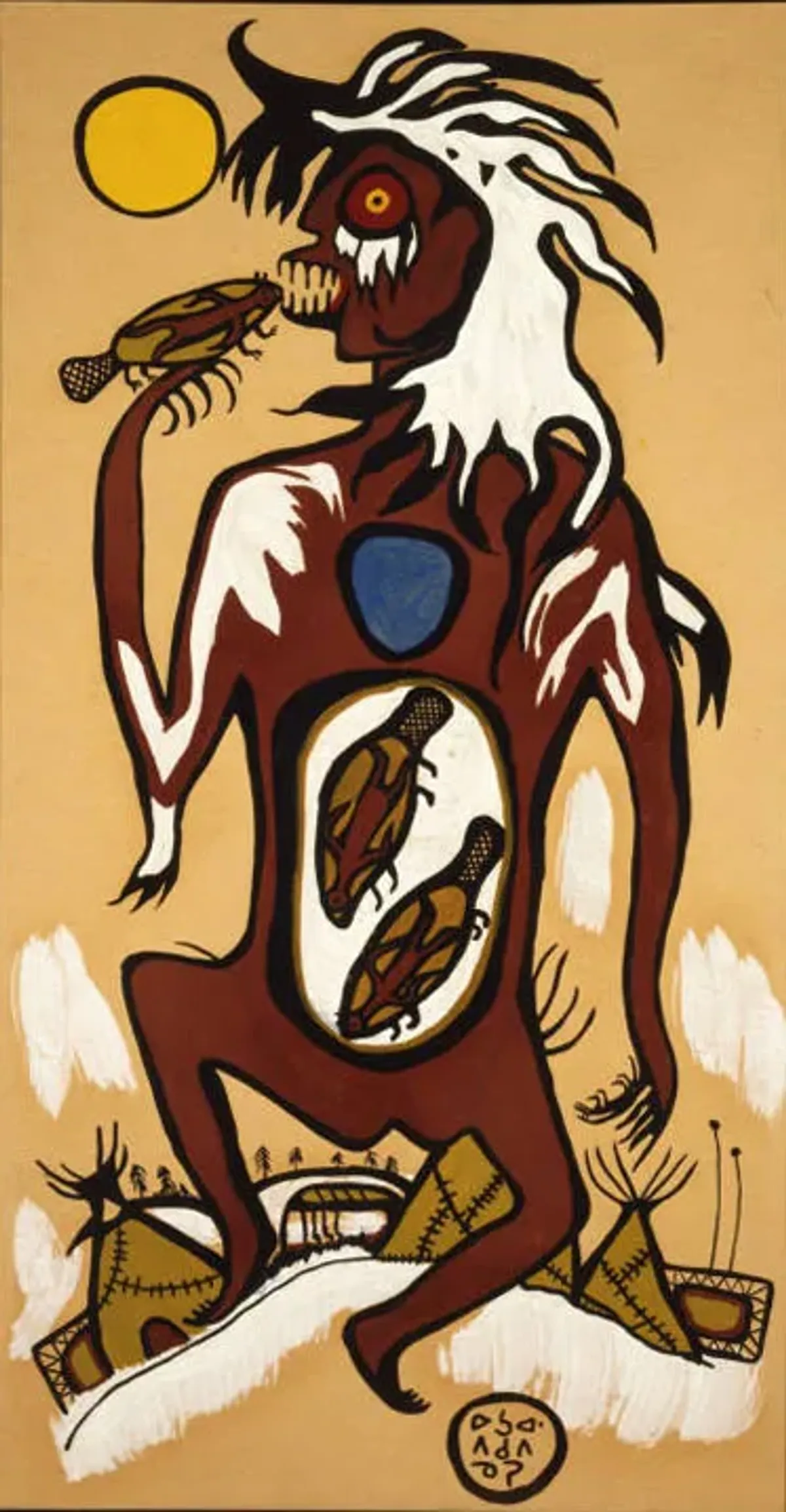

The Wendigo is one of the most misunderstood figures in global folklore. Stripped down by Hollywood into a generic horned forest monster, the true Wendigo carries a weight far heavier than any antlered skull. It is a moral warning, a cultural boundary marker, and a reflection of the harshest realities of survival in the North American wilderness.

This article presents fact-based, academically supported information drawn from peer-reviewed journals, ethnographic research, and university studies—not Wikipedia, not creepypasta, and certainly not Supernatural fan wikis.

Is the Wendigo real ?

The Wendigo (also spelled Windigo, Wiitiko, Wétiko) originates from the oral traditions of Algonquian-speaking Indigenous peoples of North America, particularly among communities in the Great Lakes region and subarctic forests of Canada and the northern United States.

These include (but are not limited to):

- The Ojibwe (Anishinaabe)

- Cree

- Algonquin

- Innu

- Naskapi

In these traditions, the Wendigo is not a cryptid. It is not a monster species. It is:

- A spiritual condition — a state of moral corruption

- A warning symbol — embodying the consequences of breaking taboo

- Sometimes a transformed human — a person who crossed the ultimate line

At its core, the Wendigo represents extreme greed, cannibalism, and the shattering of communal trust, especially during the brutal winters and famine periods that historically threatened survival.

The Environmental and Cultural Reality

To understand the Wendigo, you must first understand the environmental context in which these stories emerged:

The Subarctic Winter

- Months of extreme cold (temperatures dropping to -40°F or lower)

- Limited food sources during winter months

- Isolation — small communities cut off from others for months

- Starvation was a real, recurring threat

In these conditions, survival depended on cooperation, sharing, and collective decision-making. Hoarding food, abandoning the group, or refusing to share could mean death for everyone.

Cannibalism, while rare, did occur under the most extreme circumstances. But within these cultures, it was viewed not merely as a survival tactic, but as a spiritual and social collapse—a point of no return.

The Wendigo exists as a boundary marker for this collapse. It asks:

What happens when hunger consumes not just the body, but the soul?

Creature or Condition? The Nature of the Wendigo

Here’s where it gets complex. According to ethnographic records and oral histories:

The Wendigo as Transformation

- The Wendigo is often a human who has transformed

- Transformation is linked to:

- Cannibalism (eating human flesh)

- Extreme starvation coupled with moral breakdown

- Spiritual possession in some accounts

Physical Descriptions (When They Exist)

Traditional accounts rarely give consistent physical descriptions. When they do appear, they are deeply symbolic:

- Emaciated, impossibly tall → endless hunger that cannot be satisfied

- Hollow, skeletal → loss of humanity

- Cold, icy, frost-covered → emotional and moral emptiness

- Heart of ice → metaphor for loss of compassion

Important: The antlered deer-skull monster popularized in modern media (video games, films, internet art) is a 20th-century invention. It does not appear in traditional Indigenous teachings.

Some scholars trace this deer-skull imagery to:

- Early 1900s anthropological misinterpretations

- Visual confusion with other folkloric figures

- Modern horror media needing a “scary face” for marketing

”Wendigo Psychosis”: What Scholars Actually Say

In the early 20th century, some anthropologists and psychiatrists documented cases they called “Wendigo psychosis”—instances where individuals, often during extreme famine, expressed:

- Fear of becoming cannibalistic

- Belief they were transforming into a Wendigo

- Paranoia about being possessed

The Modern Academic Consensus:

- It is NOT a recognized psychiatric disorder

- The concept likely reflects cultural misunderstanding by early Western researchers

- Indigenous explanations were wrongly reframed as mental illness

- What anthropologists observed were culturally-framed responses to trauma and starvation stress, not evidence of a “supernatural disease”

Dr. Lou Marano (anthropologist) and other scholars argue that “Wendigo psychosis” says more about colonial-era psychiatry than it does about Indigenous cultures.

How Communities Responded to the Wendigo

There is no scientific proof of a supernatural creature being hunted. What is historically documented are community responses to individuals believed to have “become Wendigo.”

1. Execution (Most Documented)

Ethnographic records show that, in rare and extreme cases, a person believed to have fully transformed—usually after committing or attempting cannibalism—was killed by the community.

Context:

- This occurred during famine or isolation with no other options

- It was considered tragic but necessary to protect others

- The person was seen as already lost, beyond saving

Method:

- Usually swift: shooting, stabbing, or other immediate means

- The goal was protection, not punishment

2. Burning the Body or Heart

Fire appears repeatedly in accounts:

- Bodies were sometimes burned after death

- In some stories, the heart was removed and burned separately

- Ashes scattered to prevent the Wendigo’s return

Scholarly interpretation:

- Fire represents purification

- It opposes the cold, frozen nature symbolically tied to the Wendigo

- Burning ensures the corruption cannot “spread”

3. The “Ice Heart” Metaphor

Some oral stories describe the Wendigo as having a heart of ice.

This is understood academically as metaphor, not anatomy:

- Ice = emotional coldness, loss of empathy

- Melting = restoring humanity (or ensuring it cannot return)

4. Spiritual Intervention (Rare and Preventative)

In limited cases, spiritual leaders or healers attempted intervention before transformation was complete:

- Isolation from the community

- Fasting and prayer

- Ritual cleansing

These methods were aimed at preventing the transformation, not reversing it once cannibalism had occurred.

Why Pop Culture Gets the Wendigo Wrong

Modern portrayals tend to:

- Strip cultural context — turn it into a “cool monster”

- Ignore Indigenous voices — creators rarely consult or credit source communities

- Commodify sacred teachings — reduce profound moral warnings to entertainment

Scholars and Indigenous advocates widely criticize this as cultural misappropriation.

The Problem:

When you turn the Wendigo into a boss fight, a Halloween costume, or a creature feature, you erase the real human history it represents:

- Famine

- Survival ethics

- Community responsibility

- The cost of moral failure

Additional Historical Facts

Recorded Cases

One of the most famous documented cases involves Jack Fiddler (Zhauwuno-geezhigo-gaubow), an Oji-Cree chief and shaman who, along with his brother Joseph, claimed to have killed 14 Wendigoes over their lifetime.

- In 1907, Jack Fiddler was arrested by Canadian authorities for the killing of a woman he believed had become Wendigo

- He died in custody before trial (some accounts say by suicide)

- His case became a flashpoint for tensions between Indigenous law and colonial legal systems

Regional Variations

Different Algonquian groups have slightly different interpretations:

- Cree traditions emphasize the Wendigo as a spirit of excess and greed

- Ojibwe stories often focus on cannibalism and transformation

- Innu accounts describe the Wendigo as a giant with a heart of ice

The Name Itself

The word “Wendigo” likely derives from:

- Ojibwe: wiindigoo

- Cree: wīhtikow

The root meaning is debated but often interpreted as:

- “Evil spirit”

- “Cannibal”

- “One who lives alone” (isolation leading to moral decay)

The Truth, Simply Stated

Here’s what we know for certain:

- The Wendigo is culturally real—it exists as a powerful moral teaching

- It is not scientifically proven as a creature

- It reflects real human fears: hunger, greed, isolation, survival at the cost of humanity

- Communities responded with real, documented actions when they believed someone had “become” Wendigo

- The legend’s power lies in meaning, not in monstrosity

The Wendigo forces us to confront an uncomfortable question:

What happens when survival costs us our humanity?

Final Note for Readers

This topic comes from living Indigenous cultures. These are not extinct myths from a distant past—they are active cultural teachings held by present-day communities.

Curiosity is welcome. Sensationalism is not.

To understand the Wendigo is not to fear it as a monster, but to understand why it was never meant to be admired, hunted, or glorified.

It is a mirror held up to the worst parts of human nature—and a warning about what we become when we prioritize the self over the community.

Further Reading (Academic Sources)

- Lou Marano. “Windigo Psychosis: The Anatomy of an Emic-Etic Confusion” (1982)

- Nathan Carlson. “The Wendigo: A Culturally Patterned Expression” (2009)

- Jennifer Brown & Robert Brightman. “The Orders of the Dreamed: George Nelson on Cree and Northern Ojibwa Religion” (1988)

- Basil Johnston. “The Manitous: The Spiritual World of the Ojibway” (1995)

Respect the source. Respect the story.